How Shoes Are Made: Step By Step

Back in the golden age of handmade footwear the shoemaker bore responsibility for the shoemaking process from start to finish. Now it can feel like fast fashion reigns supreme but plenty of love still goes into creating handmade shoes. Now, unlike the original cobblers, high quality shoes are made using a nesting manufacturing process. So if your question is ‘how does a factory make shoes?’ this is what we’re taking a closer look at. In nesting manufacturing a factory’s various departments each performs different stages of the production process. When a department has finished their role the shoes are forwarded to the next department in line.

And unlike throwaway fashion footwear bespoke shoes undergo a surprisingly high number of different stages before they’re ready to be worn. Not every manufacturer is the same and the number of steps involved depends on the production methods they use. Looking for a ballpark figure? Let’s just say a shoe may be created in 70 steps – or it may take 390!

How Does a Factory Make Shoes?

If that number has your head spinning, you’d probably like to know exactly how shoes are made. Well don’t worry because we won’t go through those 390 steps, or even 70! We’ll just give you a comprehensive look behind the scenes at the shoemaking process.

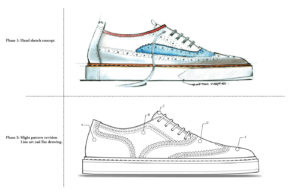

Step 1: The Design Team

Different departments are responsible for different aspects of the shoes manufacturing process. If you’re starting your own private label you’ll need assistance from prototype through to the finished product. And first up is the design department. These are the guys with the creative vision. The people who know what makes a shoe look good AND perform well. The client provides initial sketches and the in-house designers refine them to ensure they’re technically correct for the shoemaking process. Some footwear designers prefer to draw by hand, others use a computer. But each finished design will depict the shoe from multiple angles.

Different departments are responsible for different aspects of the shoes manufacturing process. If you’re starting your own private label you’ll need assistance from prototype through to the finished product. And first up is the design department. These are the guys with the creative vision. The people who know what makes a shoe look good AND perform well. The client provides initial sketches and the in-house designers refine them to ensure they’re technically correct for the shoemaking process. Some footwear designers prefer to draw by hand, others use a computer. But each finished design will depict the shoe from multiple angles.

Step 2: The Shoe Last Department

Before a shoe can go into production it needs a last. This is the physical basis on how your shoes are made. A shoe last is a mould that emulates a foot to give the shoe its shape. Traditionally these were carved from wood but now plastic and metal are also used. Every left and right shoe needs a last so its shape and size can be determined. But a last is no vaguely foot-shaped lump of wood and there are a number of things to take into account when creating one. That includes how a foot rolls when one walks and how this will affect factors such as heel height. Later in the shoemaking process the last is placed inside the shoe so it can be modelled around it. It’s used again once the shoe is almost finished to make sure the end fit matches the original design.

Step 3: Stamping and Sewing

Partly due to the sheer number of pieces used to make one shoe, constructing footwear is a true craft. The pieces needed to make the shoe are cut from high quality leather then next in the shoes manufacturing process comes stamping. Now the shoe is referred to as a shaft and the pieces of leather that make it are stamped – or marked. This is to avoid confusion when they’re sewn together. Once the pieces have been stamped they’re marked to indicate where eyelets need to be punched. If the shoe is to have perforated accents – such as a brogue – these are marked too. As are the points of the leather that will be stitched together to make a seam. The parts of the leather to be stitched are then thinned before the shaft is sent to the sewing department.

Step 4: Assembling the Shoe

The shoe is stitched and then sent to the die assembly department. No prizes for guessing that this means assembling the shoes – this is the very foundation of how your shoes are made. If the footwear is a classic Derby or an Oxford, a technique called Goodyear welting may be used.

The shoe is stitched and then sent to the die assembly department. No prizes for guessing that this means assembling the shoes – this is the very foundation of how your shoes are made. If the footwear is a classic Derby or an Oxford, a technique called Goodyear welting may be used.

Types of Shoe Construction

Goodyear welting is an intricate shoemaking process dating back to 1872. Using three nails, the first step is to temporarily attach the insole below the shoe last. Then a rubber ridge is fixed to the insole – this makes stitching the shaft to the Goodyear welt easier later. The shaft is laced and fitted over the last. It’s then attached to the insole using hot glue and nails. The next step can take anything from 30 minutes to a fortnight. This is while the shaft and last are set aside to ensure the leather flawlessly assumes the last’s shape.

The shoe is in perfect shape! It’s time to stitch an approximately 3mm wide piece of leather – a welt – to the insole and the lining. The welt is stitched into place using a Goodyear stitching machine. This takes precision to ensure the welt is as close as possible to the shaft and the rubber ridge.

The beauty of the Goodyear stitch is that because it’s on the inside of the shoe it’s completely invisible. Shoes using this technique generally don’t have a welt running all the way around the insole, omitting the heel section. Instead the shaft and insole are nailed together and a heel-shaped piece of leather, called piping, will fuse the two. When the piping has been nailed to the insole small brass pins ensure it remains at one with the shaft. Now it’s time to remove the last which has been with us every step of the journey. A shank is fitted into the shoe between the heel and front, providing support before the shoes manufacturing process continues.

Goodyear Welt v. the Blake Method

It should be pointed out that not all men’s shoes use the Goodyear welt. Another popular choice for manufacturers of bespoke shoes is the Blake method. Generally the Goodyear welt is more commonly used in British-made shoes. Particularly those crafted in Northampton, the UK’s traditional shoemaking town. The Blake method meanwhile is favoured in mainland Europe, especially in Italy. But what are the differences between the two?

Blake construction is slightly older than the Goodyear welt, dating back to 1856. Stitching cannot be done by hand and is performed using a Langhorn sewing machine. The shoemaker sews each layer of the shoe – the shaft bottom, the insole and the outsole – without welts. Those who favour the Blake will tell you their shoes are less rigid and more comfortable to wear. The Goodyear, however, is hardier and better in wet weather. (An important consideration in the UK!)

A Blake shoe has no external stitches and is normally closer cut than a Goodyear one. The upper and outsole form a tighter bond, again giving that feeling of flexibility. This is accentuated by the fact that the Blake shoe manufacturing process uses less layers. Goodyear welt shoes have more layers providing that more durable construction that serves style conscious men in damp climates better! However if wet weather is not an issue, how your shoes are made will be of less importance. Providing they’re stylish, well made and help you, or your customers, stand out from the crowd!

Step 5: Step Insoles and Decoration

If you’re starting your own shoe line, you’ll be pleased to know your shoe is taking shape rather nicely. But it’s still not looking particularly stylish and its inner is still on the rough and ready side. To address this a filler layer is added. To ensure comfort and movement the filler must be flexible so cork is normally used. This will even out the foundation for the insole which will be glued, and then securely stitched, to the welt.

As you’ve probably gathered, how shoes are made is no mean feat of craftsmanship! But our shoemaking process isn’t finished just yet. Now the pins that were placed in the heel will be removed and the holes they’ve left in the leather sealed. Any ornamental perforation is taken care of at this stage. Or if the finish of the shoe is smooth, seam holes are carefully hidden through a procedure of ironing, dyeing and polishing. Next, the edge of the heel and its outsole are abraded and the visible part of the welt is decorated. The double seam is compacted next and the heel and tips of the sole are dyed. Last but not least, a half-insole with the brand’s logo is inserted and the shoe is carefully cleaned.

Step 6: The Shoe Room

You know nearly everything when it comes to learning how to get shoes made. And we’re nearing the end of our journey. Last stop: the shoe room. This might sound like a dream come true for footwear aficionados. But rather than being a walk-in closet full of brogues and boots, this is where shoes go for one final loving caress. This is the finishing department where bespoke shoes receive the finishing touches that set them apart from their cheaper cousins. The shoes are polished until gleaming and, if the style requires it, they are laced up.

Each and every shoe then undergoes a thorough final quality check. Then they’re packaged and shipped to the retailer, ready for a discerning customer – you!? – to purchase and wear with pride.